Cren Sandys-Lumsdaine

&

The Calcutta Light Horse

DWIGHT JON ZIMMERMAN

Cren Sandys-Lumsdaine

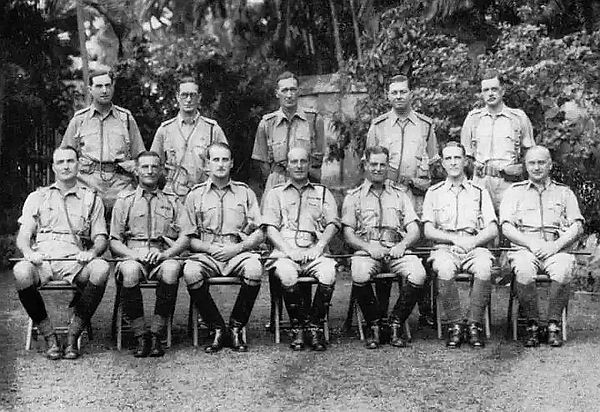

For decades the Calcutta Light Horse, a 186-year-old British auxiliary regiment, was more a social club than territorial regiment. Now its members, some of whom were veterans who had seen service in World War I, and despite their patriotic commitment in service in this unit, were resigned to watching from the sidelines as a new war was being waged around them. Then the Special Operations Executive (SOE) gave these old warhorses an opportunity for some covert derring-do that seemed more in keeping with Hollywood. On the night of March 9-10, 1943, volunteers from Calcutta Light Horse, assisted by some volunteers from Calcutta Scottish, another auxiliary regiment, conducted Operation Creek – arguably the most improbable SOE mission of the war. Their mission: Capture or sink the German merchantman Ehrenfels.

The Ehrenfels was one of four Axis merchantmen (three German, one Italian) in the region when war broke out in 1939. All immediately sought refuge in the nearest neutral port, in this case Mormugao, Goa. Located on India’s western coast about 300 miles south of Bombay (Mumbai), Goa was at the time a Portuguese territory. British authorities were aware of the ships’ presence in Goa, but as these were merchantmen, not warships, they were not seen as a threat. That perception began to change when 46 Allied merchantmen were sunk by U-boats in the Indian Ocean over a six-week period in the fall of 1942. The toll continued to climb. Twelve ships were sunk in the first week of March. At this rate, the U-boats would be able to completely blockade India. Eventually SOE India determined that the U-boats were getting detailed intelligence about merchant ship schedules, routes, even cargo, through a network of pro-Axis Indian agents providing information to the Ehrenfels which, in violation of neutrality laws, was passing the information to the U-boats via a secret radio transmitter.

Because Goa was neutral, a military operation was a non-starter. But a group of British civilians, using the cover story of a sea-going vacation-cum-drunken-dare boarding party gone awry (together with some well-placed bribes to Portuguese territorial government officials), could get away with an attack on the Ehrenfels.

Maybe.

Such was the basic idea behind Operation Creek. That such a mad scheme was not only considered, but also approved, is a testament as to how desperate the maritime situation had become. Lt. Col. Lewis Pugh was SOE India’s Director of Country Sections, part of Force 136 that conducted covert missions. In the latter half of February, he contacted his friend Bill Grice, the colonel of the Calcutta Light Horse, and after swearing him to secrecy laid out the basic facts. Pugh needed 15 to 20 men. Their target was the Ehrenfels, which they would either capture or sink. The mission would last about two weeks. The volunteers would be given some crash commando training. Because it was a top-secret mission, they’d get no credit, no pay, nor pensions should anything go wrong, and no medals. Grice wryly observed, “How attractive you make the conditions sound, Lewis.” But Grice agreed to call a special meeting to ask for volunteers.

The following evening, Grice addressed an assemblage of about 30 members, stating that he needed 18 volunteers for a secret mission against the Germans. “I can tell you nothing about it except that the operation should take about a fortnight and will involve a short sea voyage. There it is, gentlemen. I leave it to you. Is anyone willing to volunteer?” To a man, everyone raised his hand.

The culling commenced. Those clearly too old or in poor health were dismissed. Among the accepted was the unit’s corporal, Bill Manners, who asked, “What about me? You know I’ve only got one eye.” He had lost an eye in a school accident.

“It was good enough for Nelson,” replied Grice, referring to Adm. Horatio Nelson, the hero of Trafalgar. “Why shouldn’t it be all right for you?” Insufficient men remained after the culling, and four members from Calcutta Scottish, another auxiliary, completed the roster.

Commando training was basic and brief. In addition, the men studied blueprints of the Ehrenfels obtained by SOE and practiced boarding procedures. When the time came to carry out Operation Creek, to avoid arousing suspicion, they traveled separately in small groups by train to Cochin (Kochi) on the southwest tip of India where they rendezvoused with the ship that would take them to Goa.

The raiders of Operation Creek expected to find in the harbor a destroyer, or a landing craft. At worst a trawler. Instead, to their astonishment they found themselves boarding what was indisputably the most unlikely warship ever used in World War II.

The 18 men in Operation Creek were the most unlikely ever to participate in a special operations mission – middle-aged, overweight, and decades removed from active military service. The auxiliary regiments in which they were members, the Calcutta Light Horse (most) and Calcutta Scottish (four), were more social clubs than military units. But, because they were civilians who once had served in the military, they were Special Operations Executive (SOE), India’s only hope in Operation Creek – the capture or sinking of the Ehrenfels, a German merchantman-turned-spy ship, one of four Axis ships anchored in Mormugao harbor in the neutral Portuguese territory of Goa.

The pre-mission plan called for the men to travel from Calcutta to the southwest Indian port city of Cochin (Kochi) where they would rendezvous with the ship that would take them north to Mormugao. But instead of an expected warship or trawler, Calcutta Light Horse Col. Bill Grice and Operation Creek leader Lt. Col. Lewis Pugh of SOE India showed them the Phoebe, a hopper barge used to dredge rivers, the only available vessel, captained by Cmdr. Bernard Davis of the Royal Navy.

Meanwhile, Light Horse member Jock Cartwright was in Mormugao using funds provided by SOE to secretly arrange the diversion. To reduce the number of crewmembers aboard Ehrenfels on the night of the attack, a ruse was devised involving a lavish festival and free prostitutes. Officially the festival was for all the officers and sailors of ships in the harbor. Cartwright bribed key government officials and made the appropriate financial arrangements with the brothel owners. On the night of March 9, 1943, with the festival in full swing and the brothels bustling with sailors, everything was ready for the boarders.

At about 2:30 a.m. March 10, the Phoebe’s hull ground against that of the Ehrenfels. Immediately the men of Operation Creek, led by Pugh, threw their grappling irons, clambered up makeshift boarding ladders, and began to fan out, Sten guns and explosive charges at the ready, to accomplish their assigned tasks.

Earlier, the captains of the Axis ships had worked out individual defensive measures in the event of such an assault. An attacked ship would also blast a siren warning. Finally, they agreed to scuttle their ships to avoid capture.

Surprise was on the attackers’ side, and response by the skeleton crew on the Ehrenfels was slow and uncoordinated, in part because her captain was among the first killed. Though the radio codebooks were destroyed, Pugh captured the transmitter. Twenty minutes into the raid, Davis on the Phoebe noticed the Ehrenfels beginning to list. Some members of the Ehrenfels’ crew had opened sea valves, letting in tons of seawater. Immediately Davis ordered the lines to the Ehrenfels cast off, and pulled three times on the ship’s horn, the signal for the attackers to return to the Phoebe.

Astonishingly, all the attackers returned to the Phoebe safely, with some suffering only minor injuries. Then they heard a series of explosions on the other Axis ships. Fearing an attack, the other captains had preemptively scuttled their ships.

As Davis guided Phoebe out of the harbor before Portuguese authorities could intercept her, Pugh transmitted to headquarters the code word “Longshanks” – meaning all Axis ships sunk.

U-boat attacks plummeted. For the rest of March, U-boats sank only one ship. In April, only three merchantmen went down.

Meanwhile the volunteers of the Calcutta Light Horse and Calcutta Scottish returned to their civilian careers. One such volunteer was Jack Breene, a partner in an insurance firm. As he settled in behind his desk to tackle business that had accumulated in his absence his partner entered, a worried look on his face. The partner handed Breene a newspaper, pointing to an article about the sinking of the Axis ships in Goa. Acting innocent, Breene looked at his partner, asking what that had to do with anything. His partner replied, “Hell of a lot. Didn’t you know I’d insured the damned things? They’re worth over £4,500,000. There’ll be a claim as long as your arm.” Breene began laughing.

In 1947, with India achieving independence, Calcutta Light Horse and Calcutta Scottish stood down for the last time. Because it was a secret mission, the civilian volunteers of Operation Creek never received any honors, medals, or government message of gratitude. The members of Calcutta Light Horse designed their own memento for the mission – a sea horse – which subsequently appeared in the masthead of the organization’s magazine, and was fashioned into brooches for their wives.

The mission remained classified for decades. Then in 1978 a book about Operation Creek, Boarding Party by James Leasor, was published. Two years later, The Sea Wolves, a movie based on Leasor’s book and starring Gregory Peck, David Niven, Roger Moore, and Trevor Howard, was released. Though belated, the volunteers of Calcutta Light Horse and Calcutta Scottish finally received their due.

READ MORE

The Daring Calcutta Light Horse Raid

During a clandestine raid, the Calcutta Light Horse silenced a German transmitter

in the neutral harbor of Marmagoa.

By Robert Barr Smith

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/the-daring-calcutta-light-horse-raid/